|

|

|

|

|

Dusted Features

Another half dozen pours from the cognac of jazz labels, this time with an emphasis on titles long sequestered in the cellar.

|

|

|

|

Not Just For the Cognoscenti 2

The Blue Note Connoisseur Series has served as a reliable cash conduit for the label for quite awhile. Other series, foreign and domestic, have intersected with the line, but it continues to endure one of the most convenient means of acquiring less commercially viable albums from the vaults. The batch of six discs below, released in the autumn of last year, places welcome attention on a handful of titles that have been unusually derelict in receiving the reissue treatment. Stylistically the selections lean more to the modernist end of the spectrum, but exceptional variety is still in evidence. One certainty seems abundantly apparent in light of the uniform quality of the set; Blue Note is a still a long way removed from tapping the bottom of the barrel.

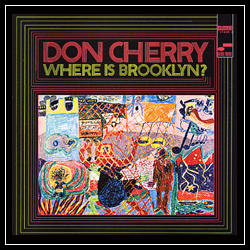

Don Cherry – Where Is Brooklyn?

The final entry in Don Cherry’s celebrated Blue Note trilogy, Where Is Brooklyn? inexplicably sat on the shelf for several years prior to its belated release in 1969. The delay may have had something to do with Cherry’s expatriation to Europe subsequent to the session. Alternatively, it might have been due to a bottleneck in the Blue Note release queue and a general belief in the superiority of the earlier two entries. Whatever the reason, this reissue has been similarly dilatory in surfacing despite its importance as a transitional venture for the trumpeter. Cherry broke with the side-long suite format of his earlier two albums, turning instead to shorter pieces that set the stage for the episodic, nearly eighteen-minute, “Unite.” The vocalic and volcanic tenor sax and quicksilver piccolo of Pharoah Sanders serve as Cherry’s foils in the frontline. Sanders was no stranger to Cherry’s music, having jousted in explosive tandem with Argentinean saxophonist Gato Barbieri just a few months earlier on the second in the series, Symphony For Improvisers. The ‘rhythm’ team of bassist Henry Grimes and drummer Ed Blackwell, staples on the entire trifecta and one of the most synergistic couplings of the era, ignite phosphorescent fires under the horns.

Sanders reels in his more recalcitrant and recondite persona, paying respect to Cherry’s themes and reserving the piercing multiphonics and nose bleed-inducing glossolalia that were the calling cards of his work with Coltrane for culminating punctuations. The decision is a welcome one that brings out elements the saxophonist’s R&B roots beautifully. The program features plenty of canny composition-smithing by Cherry and it is no coincidence that several have entered the current free jazz canon through the reverential attention of younger disciples like Ken Vandermark and Mats Gustafsson. Tracks like “Awake Nu” and “The Thing” pivot on tuneful heads that mix melodic elements of Cherry’s old employer Ornette with an overarching Aylerian ebullience. On the accelerated “Taste Maker” Cherry and Sanders spin and swirl in a cyclonic conversation while Grimes and Blackwell churn frothing rhythmic waves beneath them. The piece closes with a punishing Grimes improvisation, pregnant with string-abrading stops and birthing a massive tonal girth. “There Is the Bomb” places equal emphasis on the overlapping exchanges of the horns and the mighty undulating weave of bass and drums, a whistleable tune once again residing at the root. While the album might rank slightly behind its predecessors in terms of overall incisiveness and cohesion, it is still hardly faint praise.

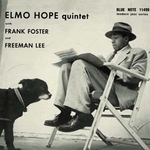

Elmo Hope – Trio and Quintet

Pianist Elmo Hope represents one of the more egregious examples of the neglected jazz genius. During his relatively short time on the planet he made earlier strides as one of the original architects of bop, squaring shoulders and holding his own with the likes of Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. Nevertheless, a derailment into drugs and booze coupled with dogged self-doubts effectively curtailed his career and eventually his life. Throughout the various lows, he thankfully still found time and resources to record and even enjoy several interludes of qualified success. Trio and Quintet offers one of the best single disc distillations of Hope’s voluminous talents, now in refurbished 24-bit fidelity that carries only the occasional age-related blemish. The disc collects music from three different sessions spanning the period of 1953 to 1957. The first date, a trio with bassist Percy Heath and drummer Philly Joe Jones in tow, finds Hope roaming through a program of ten standards and originals. Jones was one of Hope’s early devotees and he exhibits obvious pleasure in the company of his liege. Heath lays down a string of nimble lines and Hope is free to focus shaping dizzying right hand runs that preserve that First Law of bebop that mandates velocious tempos and ferocious virtuosity. The presence of elegant ballads like “Sweet and Lovely” and “I Remember You” allay any fears of ensuing motion sickness and there is even a stab at exotica with “Stars Over Marrakech.”

The remaining pair of dates expand Hope’s palette to quintet size and focus exclusively on his compositions. His writing is just as inventive and with the added presence of horns, the charts receive an extra harmonic boost. The first crew, taped in the familiar surroundings of Rudy Van Gelder’s New Jersey studio, features a frontline of tenor man Frank Foster and the slightly green around the gills trumpet of Freeman Lee. Drum dynamo Art Blakey keeps the band rocketing at a fast clip via his patented press rolls on tracks like the eponymous “Abdullah.” The discs remaining three cuts cull from a Los Angeles date that refutes the myth of the West Coast as strictly Cool territory. This time Hope’s colleagues are a crack hardbop outfit fronted by tenorist Harold Land and Shelly Manne sideman Stu Williamson. Bassist Leroy Vinnegar and drummer Frank Butler complete the group and prove why they were among the busiest rhythm duos in the city, particularly on the Bird-indebted “Vaun Ex.” Listening to Hope, it is tempting to compare his life experiences with those of his contemporary Frank Hewitt, another savant of the ivories, whose gradually growing fame is posthumous and to whom the larger jazz public continues to pay a blind eye. The sobering and obvious lesson learned from both pianists: success is so often not a function of talent.

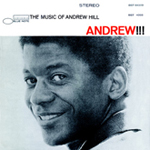

Andrew Hill – Andrew!!!

The simplicity and emphatic directness reflected in the title to Andrew Hill’s fifth album for Blue Note belies the mystery and angular ambiguity intrinsic to its compositions. It’s a disparity lacking any resonance with the relative accessibility of the music. On the contrary, Hill’s pieces probe places that are both cerebral and emotive and this album features a band particularly in tune with the pianist’s exploratory emphases. Tenor saxophonist John Gilmore, on a rare furlough from the Sun Ra Arkestra, serves as the ensemble’s sole horn. His dry multifaceted tone and advanced harmonic sense echo, and arguably surpass even that of Hill regular Joe Henderson in attunement to the composer’s more oblique characteristics. The presence of vibes in the instrumentation could easily encumber the mix, but Bobby Hutcherson’s mallets augment rather than encroach, capitalizing on the space and dynamics built into Hill’s creations to deploy floating counterpoint imbued with maximum luminosity. Hill’s own staggered, stair-stepping approach to chord-construction keeps the pieces subtly off-kilter, his right hand jumping notes in manner that brings to mind a darker, more melancholy, Monk.

Richard Davis and Joe Chambers each occupy roles well beyond conventional sideman status. The drummer’s malleable methods with meter and rhythmic color couple with Davis’ complex pizzicato patterns to create backdrops that are simultaneously densely textured and liberating to the soloists. The bassist also capitalizes on the stock placed in him by Hill, constructing a succession of solos that slingshot him into the vanguard of 60s purveyors on the instrument. As stellar as the individual playing is, Hill’s ingenious architectures are the agents that truly carry the set. The pieces are models of precocious post-bop, full of sliding metric mirrors and seamless transpositions. “Black Monday” and “No Doubt” represent the ballad delegates of the procession. Each revolves on lush cerulean themes and seamless calliope-like segues between the player’s statements. Gilmore employs a verdant voice on both, injecting his tenor with a rich tonal breadth without diminishing its innate muscularity and thrust. “Symmetry” is another standout, shaped on a mirage-like time signature from Chambers that makes the most of dusky harmonic confluence between Davis and Hill. A source of extra value, the reissue also includes strong alternate takes of “The Griots” and “Symmetry.” This is an album listenable from a myriad of ingress points, and music where the contributions of every player appeal on both intellectual and visceral levels.

Ike Quebec – The Complete Blue Note 45 Sessions

In common with his colleague Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, tenor saxophonist Ike Quebec opted for a side career as an A&R man to help him through the periodic lean years. Quebec’s post was with Blue Note and it allowed him special relationship with label owner Alfred Lion. The mutually beneficial gig arose initially out of Lion’s decision to tap the burgeoning soul jazz jukebox market of the late 50s and early 60s. He needed a robust blues-based tenor to lead various combos. Quebec’s 1940s folio for the label made him a natural pick to cut the prototype sides. Previous only available as a long out of print Mosaic box set, The Complete Blue Note 45 Sessions gathers all of the singles Quebec recorded between the summer of 1959 and the winter of 1962. The bands follow the same basic template matching his warm, virile horn with organ and drums and periodically guitar and/or bass. Tune choices are predominately boilerplate with a revolving selection of blues and ballad-oriented standards alternating with Quebec originals that do not stray too far from the same template. The recipe may be the same but the resulting music is far from boring or vacuous. Quebec’s talent at shaping endearing emotive lines and routinely spinning homespun improvisatory tales sees to that.

Due to the formulaic facets of the project and Quebec’s consistent place of prominence in the arrangements, the sidemen are somewhat interchangeable, but certain among them do standout. Organist Earl Van Dyke, who would later go on to a prolific career with Motown as a member of The Funk Brothers house band, turns in some tasty fills on tunes like “ Intermezzo” and “All The Way.” Guitarist Skeeter Best reveals twangy swing-to-blues chops on “A Light Reprieve” and “Buzzard Lope” and it’s a treat to hear veteran ivory-tickler Sir Charles Thompson ply his elegant touch on the electric console. Still, Quebec is the commanding character on stage and his breathy, Don Byas-influenced sax remains the chief draw on these sides. A rich hot chocolate tone and relaxed phrasing ramp up the romance quotient on the ballads like “Blue Monday” and “Everything Happens To Me.” Burners are in the minority, but he is just as adept at elevating the heat on more rambunctious fare like the swaggering “Later For the Rock.” Consumed in moderation the tunes are just as enjoyable and edifying in the present day as they were in the past when curious bar and club patrons could pick three for a quarter.

Jackie McLean – Consequence

A steady and methodical release schedule has accorded a nearly complete return of Jackie McLean’s entire Blue Note career to circulation. Fans of the altoist’s 1960s work know just how monumental this achievement is and newcomers to his music can thankfully now be privy too. Consequence presents him in the company of a trio of long-standing peers cycling through a program of original hardbop compositions. This is not so much McLean the intrepid explorer of such seminal outings as One Step Beyond and Let Freedom Ring but rather McLean the creative traditionalist. Trumpeter Lee Morgan was always a sympathetic frontline partner when his friend chose the latter route. Here he fits the leader’s sharp-toothed sorties hand-in-glove, especially on more frenetic pieces like the title track where a ripping alto solo rides out a slaloming rhythm straight into a note-packed salvo of brass. Contributing on a logistic level as well, Morgan supplies a pair of suitably swinging tunes for the session songbook.

Pianist Harold Mabern does an admirable job in the pilot seat of the rhythm section. His inventive right hand patterns and anchoring block chords stamp a distinctive blues flavor across much of the session whether in the context of the playful Latin progressions of “Tolypso” and “Bluesanova” or the languid ballad structure of “My Old Flame.” Drummer Billy Higgins is the other ace in the deck, his fluid sticks lacking nothing in propulsive force whether enlisted in the cause of a loping Latin beat or entrusted to launch a hard-charging succession of cymbal flares on the closing “Vernestune.” Conversely, bassist Herbie Lewis is a bit of a wallflower, but then again he is not earning a paycheck to storm the foreground. Resigning himself to the background, he supplies reliable, if unremarkable support. This is exemplary 60s hardbop and though it sits on par with easily a dozen other sessions, McLean completists and listeners with an insatiable sweet tooth for exuberantly rendered jazz of the era will probably want to add it to their collections.

Booker Ervin – Tex Book Tenor

Pardon the mediocre pun of the title and Tex Book Tenor reveals plenty of hard-swinging postbop action. Many fans of tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin have been waiting to see the session reissued, seemingly in perpetuity. The tardiness is nothing new considering that the record’s initial release was delayed nearly a decade, a slight that seems doubly confounding when one considers the explosive tandem frontline of Ervin and trumpeter Woody Shaw. The rhythm section is top flight too with relatively unknown Czech bassist Jan Arnet joining the powerhouse pairing of pianist Kenny Barron and Billy Higgins. Ervin wastes no time in winding up the tension on the brooding, Barron-penned “Gichi” with a solo that smolders with sagacious intensity. Shaw follows it up with a rebuttal that moves from cool to florid, Higgins adding audible grunts of encouragement underneath. Barron brings up the rear, improvising atop an Arnet-anchored ostinato, but the piece is stifled by an inopportune track-terminating fade.

The rest of the set maintains a comparable level of quality. Cryptic in name, “Den Tex” is straightforward in its tensile swing and it is a hard task choosing who holds the soloist crown between the two horns. Barron makes it easy, usurping the honor through a solo that evinces an uncanny communication between hands. Even Arnet gets a piece of the action with a fleeting chorus sandwiched between Barron’s close and summarizing return to theme. “In a Capricornian Way” dates itself in terms of title, but there is nary a whiff of incense and peppermints in the manner in which Ervin and Shaw sally forcefully through the call-and-response theme. Barron fills the middle with yet another bon mot of a solo and the horns take the piece out with undiminished vigor. Compared to its brethren the lightweight ballad “Lynn’s Tune” presents an uncharacteristically pedestrian turn for the band that even Ervin’s emphatic solo cannot completely salvage. The solecism is solved by the rapid-fire swing of the closing “204,” a ten-minute scorcher that tests the band’s collective faculties over the long haul and earns Ervin another avalanche of plaudits in the process. The disc also includes a succinct essay by producer Michael Cuscuna that effectively documents the highlights of Booker’s all too brief career. Those consumers with tastes oriented toward expertly executed hardbop possessing an underlying serrated edge would do well to give this long-languishing session a listen.

By Derek Taylor

|