|

|

|

|

|

Dusted Features

Dusted's Andy Freivogel lays out the slow movement of Santeria to Chicago.

|

|

|

|

A Drummer's Life: Santeria Drumming Heads North

Charles appears to be just another Chicago hipster. Depending on the day of the week, he might have facial hair, be on his way to a job at a River West art gallery, or simply be sitting in Wicker Park drawing in a notebook. One needn't spend a lot of time with Charles, however, to know the depths of his determination. Unlike the average Chicago musician, he is a student of Santeria and the bata drum, an Afro-Cuban religion that blankets the island nation, yet remains somewhat scattered across the 48 states.

“The drums tell you what to do,” he says. “You are just a servant to whatever is going on around you. At some point I just accepted that that's the way it is. Ever since I got that mindset, it's given me strength... in accepting your role as a servant, you can keep your mouth shut and accept what you're asked to do."

Charles’ view, however, doesn't arise from a sense or feeling of subservience, but more from the transcendent ideal of a religious adherent; in this case, a ceremonial drummer, an empty vessel filled by the spirit of a greater power. He is literally sworn to the drum, having gone through years of training in the U.S. and Cuba, and is initiated as Omo Anya, a “child” of the Orisha Anya, said to live inside the bata drum. The religion of his vocation, that of ceremonial drummer, thrives on the visceral connection it fosters between adherents and their guardian Orishas. Music is just one of the ways this is achieved, but its role is often misunderstood by both those within the religion, and outsiders, or ayeleros.

Playing percussion from the age of 5, Charles began walking his current path when a friend introduced him to the bata drum at about the age of 15. The friend imbued in Charles the significance of the drum, inseparable from the cultural and religious heritage that brought the bata to the New World.

"He explained to me that it was bata orisha; he taught me Eleggua (a rhythm named for the Yoruba deity),” he says. “I started learning what it was for. From the get, playing ceremonies was what it was all about. This was ceremonial music; it was clear from the start."

Drummers don't just start playing ceremonies from the first day they pick up a drum. In fact, few ascend to the position Charles holds in the Afro-Cuban religious community in Chicago. For Charles, it started with an introduction by his friend, but he followed up the recommendation with research. Between studying the rhythms his friend showed him, Charles scoured the library for books on the Afro-Cuban religion. Only after arriving in Chicago to attend the School of the Art Institute did he gain his first introduction into the religion itself, first through a santera (priestess of the religion,) and then through an Olubata (“owner of the drum,” of which there are very few in the United States).

The Yoruba religion of Ifa, which migrated to Cuba and other parts of the Caribbean largely intact from Africa, is referred to by its practitioners as Ocha, a contraction of the Yoruba word orisha, any of a broad pantheon of deities that represent the elements and conditions that make up life itself. Sometimes it's called simply la Regla, or “The Rule.” Although priests initiated to specific Orishas are called santeros or santeras, no one calls it santeria unless he or she is doing some kind of exposé on the fake news (anything other than the Daily Show) or trying to summarize an episode of CSI:Miami. The religion, by whatever name, remains the de facto national religion of Cuba, and has strong footholds in Miami, New York, Chicago and other cities on both coasts. While not exactly shrouded in secrecy, adherents of the religion practice their faith discreetly, due in part to the practice of animal sacrifice (apparently it's less dignified to offer a chicken to God than it is to put it in a box under a heat lamp), but also due to the overall stigmatization of this belief system as an African import. In fact, even the Yoruba of Nigeria are less likely to practice Ifa today than they are Islam or any number of variations of Christianity, and with the diminishing impact of Ifa on modern society in Nigeria, its music must grow in other places.

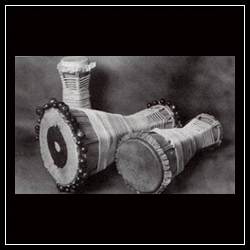

The bata drum, originally from Nigeria, consists of an hourglass-shaped body with a large head on one end (the enu or mouth) and a small head (chacha) on the other. While Nigerian bata ensembles have included (and can still include) up to four or five different drums, bata in the Afro-Cuban religious context are played, and in fact born, in sets of three: the Iya (the “mother,” the largest of drums and the most difficult to master,) the Itotele (the medium-sized drum) and the Okonkolo (“the little daughter,” acting almost as a metronome for the intricate interplay between the Itotele and Iya.) The drum is played on the lap of the drummer, with one hand striking the enu and the other hand striking the chacha. While Western music has a habit of handing off the biggest instrument to the least skilled player in the band, the Iya is the drum upon which the most intricate rhythmic patterns are played, patterns that act as codes to instruct the other players. The Iya player takes his cues from an akpwon (singer), whose job it is to praise the Orishas during a toque (a “touching” of the drums, or a ceremony in which the drums are played to call down the Orishas). The akpwon invokes “hot” verses to incite and provoke the Orishas to possess some of the practitioners at the toque.

While the drummers may react to the energy and dynamics in the room at a ceremony, the focus becomes playing, as a unit, an ancient repertoire of rhythms, or toques, each dedicated to a specific Orisha. Charles epitomizes the role of the drummer in ceremony as a microcosm of community and interpersonal relationships.

"Three drums fit together... it's like a social model,” Charles says. “Three people have a way of communicating; you have to be exactly on the same page or it doesn't happen. When it does happen, it's beautiful…for one thing, everything becomes very clear and easy in the music, because you're not fighting. When (the drummers) become one, the drums are talking, and the three drums become one drum. That's when Anya speaks. That's when the santo comes down.”

The arrival of an Orisha in the room is a blessing, but most present at a toque lack the spiritual strength to carry the energy, so the akpwon often shifts his or her tune, reverting to “cool” verses that placate the present Orisha. Bringing down the Orisha is the often the only evidence that the drummers have done their job. Outside of that shining moment, few within the religion, let alone ayeleros, are quick to recognize or acknowledge the crucial role they play. In Nigeria, drummers are known to line up outside the ile (house) where a ceremony is scheduled to take place, just for a chance to play for their supper, only to be chased away. Sadly, this attitude persists today, in the apartments and bungalows of Chicago that function as a veritable underground version of the Afro-Cuban religion.

Over the years, some of the great percussionists of Latin Jazz and Salsa have lived the same dualistic existence as Charles, including Tito Puente, Francisco Aguabella, Giovanni Hidalgo, and even Headhunter great Bill Summers, all of whom held choice day jobs. For now, Charles says, a day job is pretty much a necessity. While ceremonies couldn't occur without drummers, the pay is nearly non-existent. In the fascinating alternate economy of the religion, everything has it's fee, whether it’s for the consultation of a babalawo (a priest with the ability to divine events and proper courses of action), chickens from the live poultry store, herbs and plants flown in from Miami, or the elaborate “throne,” an almost art-like installation that includes mounds of fruit, coconuts, flowers and shiny fabrics.

"Being a drummer definitely has its place in the religion,” Charles concludes. “I'm basically hired to just provide a service, and do it with poise, and do it with feeling, and do it well. … I'm not doing it for anything other than the fact that it's my path, my meditation. If I don't do it, I'd be missing a part of me."

By Andy Freivogel

|