|

|

|

|

|

Dusted Features

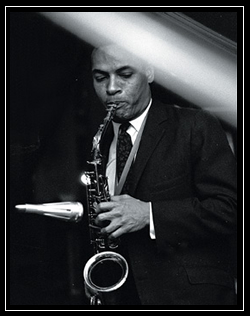

Ayler Records' labor of love pays homage to the unsung altoist of free jazz yore, Jimmy Lyons.

|

|

|

|

Lyons' Pride

When Paul Desmond started recording as a leader in late 1954, he and his employer Dave Brubeck ironed out an agreement. The gist of the unwritten pact stated that the alto saxophonist would not involve piano, Brubeck’s instrument, in any of his solo ventures. Jimmy Lyons and Cecil Taylor seem to have struck a similar bargain. None of Lyons’ solo recordings incorporate piano and the same holds true for six-plus hours of music issued on this sumptuous five-disc Box Set by Ayler Records. Proof of his talent and creativity, Lyon’s melodic and harmonic facility makes the absence hardly noticeable. His compositions actually work better without a chordal anchor to ground them, and there are plenty of examples in this set that bear this claim out.

The first disc captures a September 1972 gig at the Sam Rivers-run Studio Rivbea. Sound is surprisingly clean, with clear separation between the instruments and Hayes Burnett’s bass especially well preserved by the sonics. The responsive repartee between Lyons and trumpeter Raphé Malik can’t help but recall the synergy shared by the more widely touted team of Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry. The horns bounce note clusters back and forth, engaging in a series of sprinting chases that also highlight stylistic differences between the two. Malik alternates staccato bursts with longer lyrical arcs, while Lyons, sounding limber and expressive, races through lithesome lattices of notes.

Drummer Sydney Smart favors volume over finesse and his trip-hammer sticks propel the band at high speeds. He quickly has the audience shouting and cheering with delight and pulls out the stops for blustery bookending solo on the first leap through Lyon’s signature “Jump Up”. “Gossip” fades in with the quartet already in the throes of a velocious exchange. Once again Smart’s drums sound off at stentorian levels and Burnett has to pummel his strings vigorously in order to be heard above the crashing cymbal tide. Lyons’ phrasing is a bit brambly in spots as he surfs the frothing rhythmic breakers summoned by his colleagues, but Malik’s steady brass is a model of attentive and carefully meted energy from start to finish.

“Ballad One” packs in more emotion than its generic title might imply. Gliding through a loosely harmonized head, the horns eventually defer to Burnett who builds a deep thrumming statement from the bottom reaches of his fingerboard. Sans the militant zeal of Smart, the bassist finally has space to move. Lyons’ own extemporization sounds somewhat tentative. Malik makes up the difference again with a lattice of poignant brassy lines. Their colloquy later in the piece comes across as more cohesive and Lyons seems more at ease. “Mr 1-2-5 Street”, another up-tempo piece with an accelerated angular theme, quickly diverts into individual solos by the horns. Burnett and Smart propel the piece at a rapid-fire pace, goading Malik toward some truly ferocious blowing.

A second version of “Jump Up” covers nearly twice the ground of its predecessor. Lyons sounds more focused, riding out the rushing swells of Smart’s drums with florid swathes of notes. Even so, Malik and the drummer end up the true lodestones of the piece, the former through an extended solo and the latter in a closing statement that shows off strong polyrhythmic propensity not as present in his earlier work. Compared to the original compositions, the clipped reading of “Round Midnight” that closes the concert seems more like set filler, but it’s still enjoyable to hear the quartet tackle such a shop-worn jazz standard.

Disc Two turns the calendar pages forward nearly three years to another Rivbea gig circa summer 1975. Burnett still holds down the bass chair, but the drum stool is now home to one Henry Letcher. Two sprawling pieces, “Family” and “Heritage”, comprise the set. Each is monolithic in size, but far from monosyllabic in scope. Communal connotations inherent to each track title are borne out in prolonged improvisations that make full use of the trio’s collective powers. Lyons sounds challenged by the dearth of a second horn foil and the set’s notes do make mention of the ways in which his compositions were commonly more suited to multiple frontline voices. He adapts well to the leaner configuration and ends up showing off facets of his on-the-fly ingenuity that stand up beautifully under scrutiny.

“Family” takes up over 40 minutes and expands from a sirocco of flurried alto scribbles. Burnett and Letcher stoke a vertical momentum, framing Lyons’ fleetly-quoting lines with a flexible array of rhythmic accents and commentary. The bassist is again slightly compromised by the recording mix, particularly during his arco passages, which lose some of their harmonic lucidity in proximity to Letcher’s more tumultuous traps play. Lyons own extended sortie rivals late-period Coltrane in terms of loquacity. It’s 25 glorious minutes before he takes the reed out of his mouth and defers to his partners. Burnett’s successive long-form exploration of his strings makes versatile use of pitch variations, high resonating harmonics and percussive repetition. Letcher chooses an equally variable tack, moving from quietly textured frugality through incremental increases in density and velocity.

“Heritage” occupies only slightly less time than its predecessor and sacrifices nothing in terms of skillful execution. After a terse prefatory exchange between Burnett and Letcher, Lyons arrives with a series of piquant melodic elaborations, playing fast and furious from the outset. Hitting stride early, he hunkers down for the long haul and jockeys through squealing note streams with impressive speed and alacrity. His partners show similar dedication and the mileage of the piece scrolls by with several solo and ensemble detours along the way. The sum is at once unrelenting and exhilarating as all three men barely pause for breath and maintain a stamina-taxing level of intensity for the majority of the piece. Bass and drum solos eventually give way to Lyons in a more reflective mood, revisiting the melody of “Jump Up”. Periodic tape dropouts mar the action, but the marathon run stands as a memorable achievement in spite of these minor blemishes.

The second Rivbea set concludes on Disc Three with a more concise reading of “Heritage”, less ambitious than its predecessor, but still brimming with bracketed energy to spare Most of disc’s running time is devoted to a solo Lyons performance taped at Soundscape in April of 1981. The solitary setting brings both his melodic acuity and the wide repository of patterned phrases that constituted his vocabulary into bold relief. Breaks based on shifts in thematic content divide up the concert into individual tracks, but Lyons quotes freely over the expanse of the entire recital. Digested in a single sitting the concert can feel like a daunting prospect. But the chance to hear Lyons’ alto alone and at length on record, something heretofore not possible, is something to savor just the same.

“Clutter” reels out as a chain of melodic links that incorporate kernels of Lyons’ own compositions along with paraphrases of standards like “It Might As Well Be Spring” and Monk’s “Bemsha Swing”. His tone is clear and confident and while the improvisations have an air of the academic about them, the sincerity audible in Lyons’ spontaneous inventions delivers a staggering emotive punch. “Mary Mary”, a line written for pianist/composer Mary Lou Williams, references cells from other pieces in Lyons’ repertoire. The next two tracks, “Never” and “Configuration C”, sound more like sketches and each transpires in quick succession. The lengthier “Repertoire Riffin’” engulfs nearly a quarter of an hour in its methodical dissection of a clutch of component riffs. “Impro Scream” finds the altoist trying on a variety of tonal hats through a quick bout of aggressive blowing that unleashes an uncharacteristic gush of multiphonics for added effect.

Disc Four presents Lyons in the company of bassoonist Karen Borca and drummer Paul Murphy, colleagues who would follow him to the end of his career. Both were regulars on his final albums and each is fine form on the set taped at a concert in Geneva, Switzerland in May of 1984. Borca was also Lyons’ life partner and a principal source of support during the various tribulations the altoist would endure in attempting to actualize his musical goals. Her presence as second horn effectively counterweighs the absence of bass as formal harmonic anchor. For his part, Murphy demonstrates an Olympian brawn behind the drum kit, fueling each of the pieces with tumbling press rolls and driving beats. The trio’s songbook borrows in part from Lyons’ contemporaneous Black Saint records with a playful take on “Wee Sneezawee”, kicking the concert off at a rapid clip.

Lyons gallops out of the gate in a swiftly darting succession of lines. Borca’s heavier double reed answers by navigating the lower registers in coarsely wound legato braids. Adopting the weight and girth of a baritone saxophone, her horn retains the enviable agility of an alto in an instantly engaging display of skill. Murphy belts his skins with blurred sticks, conjuring up a rhythmic core around which the horns twine in tightly angling arcs. His short solo near the opening track’s close gives but a small indication of the amount of energy he has bridled within his tautly-flexed sinews. For the pathos-rich ballad “After You Left”, the trio trades wanton energy for slowly developing counterpoint and call-and-response. Murphy responds in kind, moving to brushes and engaging in sympathetic conversation with each of the horns individually and in tandem.

The bebop inflected “Theme” works off more close interplay between Lyons and Borca. The saxophonist is at his most lubricious, firing off ideas at speeds that require Murphy to keep up on the demanding rhythmic front. Keep pace he does, while once again showing himself as more than up to the task of propelling the trio in both metric and free contexts. “Shakin Back” resituates the trio back in humor-ripe surroundings. The horns shimmy and shake through a simple swinging theme while Murphy whittles out a syncopated string of beats behind them. Borca’s contradictory “Good News Blues” closes the concert on an upbeat note and finds the composer blowing the hell out of her bassoon. There’s even the intrusion of what sounds like festival security walkie-talkie banter on the monitors during Murphy’s closing solo. A short radio interview segment taped at WKCR-FM in the summer of 1978 rounds out the remainder of the disc. It’s an all too brief exchange, but a fascinating listen just the same. Lyons touches on his early musical education, his initial years with Cecil and the synonymous nature of composition and improvisation.

The set’s final disc documents the trio on disc four with the added muscle of William Parker’s bass. Recorded at a Tufts University gig in February of 1985, the music finds the band running through familiar tunes along with a few new ones. Curiously enough, the fidelity here is the least accommodating of the set, surprising since the recording is of the most recent vintage. Fortunately any audio foibles wither under the might of the music and the quartet succeeds in giving the students, faculty and general audience quite a show. Curiously enough, the first two tunes in the set list are the same as the Geneva gig from nearly a year earlier, even clocking in at close to analogous times.

Parker contributes a welcome bottom end to the band and his amplified pizzicato figures mesh athletically with Murphy’s fields of cymbal and snare electricity. Lyons’ usual quicksilver lines are a bit recessed in the mix and there are times when he has to vie with the rhythm section’s vociferousness to be heard. But the raw fidelity is a small price for the concentrated energy on hand. Borca is less compromised by the slightly stilted sound. Her snaking, stoutly planted phrases slide and shout atop the clamorous backgrounds built up by Murphy and Parker and once again she makes her double reed speak in demanding tongues.

Alongside tried and true numbers like “Shakin’ Back” and “Gossip”, the latter an incomplete take; the quartet also tries out a pair of new compositions. “Tortuga” takes shape in a customary theme-solos progression, opening with a gorgeous echo-laden a capella by Lyons and Borca. “Driads” is more intricate in design and undertaking. Parker wields his frenzied bow along with tugging fingers and his anchoring harmonic structures serve as orbital center for the spiraling circular forays of the horns. Murphy crafts a near continuous wash of metallic static that further augments the tension and Lyons sounds at his most ebullient in a soaring solo that attains supersensory heights. Collected in sum, this date delivers one of the most consistently galvanizing highlights of the entire box.

Lyons succumbed to lung cancer in May of 1986, a sad fate echoing that of the recently deceased Frank Lowe. In light of his extremely finite discography, the manna of the set is obviously the music, all of it previously unreleased. But the package and accoutrements are also worthy of praise. An accompanying 60-page booklet, littered with archival photos, includes in-depth essays on Lyons career and music by Ben Young and Ed Hazell. The box itself is a model of economical and esthetic beauty with the five discs housed in lightweight cardboard sleeves. There’s also added value in that each disc is crammed nearly to capacity with music. Jan Ström and his partners at Ayler Records have come up with a celebratory set worthy of Lyons’ memory and legacy. Limited to a modest pressing of 500 copies, it’s sure to sell out fast.

By Derek Taylor

|